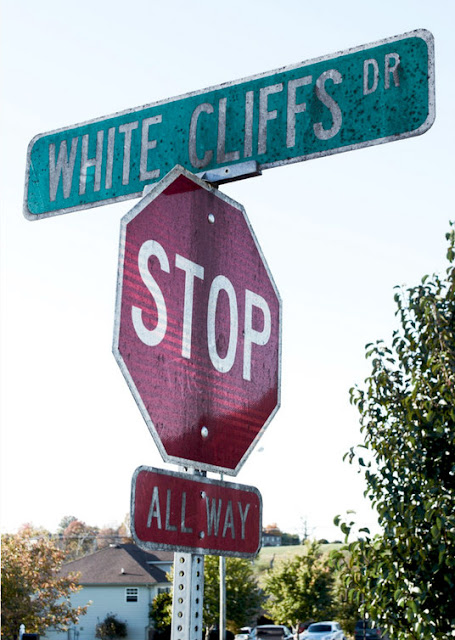

For people who live in the area of Frankfort, Kentucky, a black fungus covers their homes. That’s because Baudoinia compniacensis — commonly known as “whiskey fungus” — grows all over the neighborhood. It’s on stop signs, porch furniture, siding, fences, basketball hoops, and cars. It has even been found growing on the dome of the Kentucky state capitol building. From a distance it looks sooty, but up close it looks like thin, black felt. Anything left untouched for years ends up looking like it’s been burnt to a crisp. A French scientist named Antonin Baudoin first studied this “plague of soot” in 1872, after noticing it on distilleries in Cognac, France. Kentucky makes 95% of the world’s bourbon, and in Frankfort large warehouses hold stacks of bourbon left to age in charred oak barrels, a process that takes a couple of years. During this phase, an estimated 2% to 5% of the alcohol evaporates, and that can add up to as much as 1,000 tons of ethanol emissions every year. In the bourbon world, the lost ethanol is referred to as “the angel’s share,” suggesting that ethanol vapors reach the heavens. Ethanol is like flying sugar, and when it combines with a hint of moisture — say, morning dew or humidity — whiskey fungus develops and lands on anything in the area. Most people in close proximity to the distilleries have their homes power-washed every couple of years, watching their homes go from dingy to sparkling white, at least temporarily. Despite the nuisance — and the expense — those who live with whiskey fungus say it’s a small price to pay for the jobs the distilleries provide.

Kentucky's Bourbon Industry Is Covering Its Neighbors In Black Fungus

For people who live in the area of Frankfort, Kentucky, a black fungus covers their homes. That’s because Baudoinia compniacensis — commonly known as “whiskey fungus” — grows all over the neighborhood. It’s on stop signs, porch furniture, siding, fences, basketball hoops, and cars. It has even been found growing on the dome of the Kentucky state capitol building. From a distance it looks sooty, but up close it looks like thin, black felt. Anything left untouched for years ends up looking like it’s been burnt to a crisp. A French scientist named Antonin Baudoin first studied this “plague of soot” in 1872, after noticing it on distilleries in Cognac, France. Kentucky makes 95% of the world’s bourbon, and in Frankfort large warehouses hold stacks of bourbon left to age in charred oak barrels, a process that takes a couple of years. During this phase, an estimated 2% to 5% of the alcohol evaporates, and that can add up to as much as 1,000 tons of ethanol emissions every year. In the bourbon world, the lost ethanol is referred to as “the angel’s share,” suggesting that ethanol vapors reach the heavens. Ethanol is like flying sugar, and when it combines with a hint of moisture — say, morning dew or humidity — whiskey fungus develops and lands on anything in the area. Most people in close proximity to the distilleries have their homes power-washed every couple of years, watching their homes go from dingy to sparkling white, at least temporarily. Despite the nuisance — and the expense — those who live with whiskey fungus say it’s a small price to pay for the jobs the distilleries provide.